MMVSL

MUSEO MEMORIAL VILLA SAN LUIS

Competition Entry / 2nd Prize.

Design Team:

Daniel Lazo, Gabriel Cáceres.

Collaborators:

Tomislav Mímica, Diego Melero.

Location:

Las Condes, Santiago de Chile

Built Area:

800 m2

Project Year:

2025

Materials:

Concrete, steel, glass.

Renders:

Tomislav Mimica

PROJECT OBJECTIVES

How can a museum be designed within the ruins of the very testimony the museum seeks to rescue and enhance, without sacrificing the authenticity of that testimony? How can this be done so that, despite the necessary alterations to which the ruin will be subjected, the museum makes this testimony something evident and unavoidable to its visitors? And how can it be integrated into the city and the complex that houses it, after being for years a symbol of conflict, of a disputed terrain?

The memorial museum project seeks to answer these major questions expressly posed by the competition.

STRATEGY

To accomplish this objective, three considerably simpler questions derived from the brief must be answered first:

1. Area. How can an 800 sqm memorial museum be designed within the existing 910 sqm chassis of a residential building? Logic dictates that the difference in surface area between the existing and planned areas must be resolved through demolition. Given that at least 70% of the existing structure must be preserved then: what should be demolished?

2. Change of use. The transformation of a building from residential use to a public use, such as the memorial museum, entails an increase in the load to which the structure will be subjected—for the simple fact that it will have to accommodate a much larger number of users than originally planned—therefore, the structure must be reinforced. Since the budget is limited, reinforcing the entire structure—although it may sound logical—is counterproductive. All museums have a considerable number of spaces inaccessible to the public, so reinforcing them is a waste of resources. Considering also that the commission requires preserving the imprint of the original building, then: what should be reinforced?

3. Program. While historically, it is common to find that many museums exist within structures that were not originally designed for that purpose (the Louvre in Paris was a military fortress and later a palace before becoming a museum; the Tate Modern in London was a power station), and in particular, that exhibition spaces inhabit buildings of the most diverse types, including residences and apartments, the truth is that under ideal conditions, residential and museum programs require different spatial characteristics: lighting, air ventilation, public circulation, etc. In turn, different ways of reinforcing structures produce different spatial characteristics. Broadly speaking, we can identify two types of reinforcement: stereotomic, composed of solid elements such as walls and slabs; and tectonic, rigid diaphragms of beams, columns, and braces. It is logical, therefore, to assume that the way a structure is reinforced is fundamental to reconciling the differences between the spatial requirements of the different programs. So, then: how to reinforce?

While these three questions may seem strictly pragmatic, the product of a clinical analysis of the brief and disconnected from the actual content of the new museum, truth is that the answers arise directly from that content and seek to fulfill the project's larger objective.

The Memorial Museum proposes three themes that shape each answer.

THE MEMORIAL MUSEUM AS A NARRATIVE SUPPORT

Museum and exhibition spaces stand out for being eminently spaces of circulation: they contain movement. While they allow for permanence, when it occurs, it is temporary. They also suggest a speed for that movement. Depending on the type of exhibition, this wandering can have a direction—which the visitor can follow or ignore. Museums are like books; they can tell a single story, like a novel with different chapters, or compile a set of stories that share one or more themes, like an anthology. In the case of the MMVSL, the memorial museum tells the true story of a group of buildings and the community that inhabited it, with their struggles, triumphs, and tragedies over a period of more than six decades. Its history is also an inescapable reflection of the country's recent history, of the human tragedy of the dictatorship, and of the city of Santiago in particular. From an academic perspective, it is also a reflection of the paradigm shift surrounding urban planning in Chile, from a centralized model to a free market one.

This history is divided into three chapters, each with distinct thematic emphases, but which maintain a unity. It is a single story. Each chapter provides vital information for understanding the next. There is directionality in the narrative and therefore in the movement within the museum.

This idea, however, is in conflict with the architectural reality of the existing building. Due to the nature of its residential use, each space is independent from the previous one; they are connected only by a vertical circulation core that distributes to each space per floor. Even in its current state, with part of its interior divisions removed, the floor plan is divided into four quadrants. There is no directionality in the route.

The proposal seeks to correct this through the selective demolition of slab areas (what should be demolished?), allowing a vertical connection between floors. It is selective because, to keep costs under control and preserve the imprint of the original building, it was decided to isolate the demolition to only the eastern hemisphere of the structure.

This operation allows for the creation of three large double-height spaces containing each chapter of the exhibition. The position of the demolition determines that each gallery occupies the quadrant opposite the gallery on the floor below, so they always share a connecting floor. This creates a vertically snaking path—the visitor must pass through one room to reach the next—suggesting a direction to the wandering.

THE MUSEUM AS A SOCIAL CONDENSER

Museums, unlike other exhibition spaces, such as art galleries, are distinguished by a public and educational vocation. This means that, along with the spaces that house the exhibition, they offer other complementary spaces that operate simultaneously—regardless of whether the visitor visits the exhibition or not—broadening the spectrum of audiences the museum serves. Contemporary practice has well understood this potential impact and has turned several museums into destinations not only for culture but also for meeting and community. By becoming true social condensers museums across the world welcome daily thousands of citizens who visit them regularly and free of charge, whether to meet someone, eat, or seek shelter from the weather. This logic allows the museum's impact radius to expand to an urban scale, and also helps fund the building's operation.

Based on the building's structural history, it is known that the change in use from residential to museum implies that those areas designated for public use must be able to withstand twice the load overload that the structure currently withstands – from 200 to 400 kg per sqm. Therefore, the definition of these areas, and how the program is laid out within the building, is key to answering the second question: what should be reinforced?

The project proposes dedicating the east side of the block to exhibition spaces, which, due to the demolition involved, requires reinforcing this area in its entirety.

For the west side, the proposal seeks to minimize the intervention areas in order to maintain the imprint of the original building. The program's layout within the western hemisphere is proposed as follows:

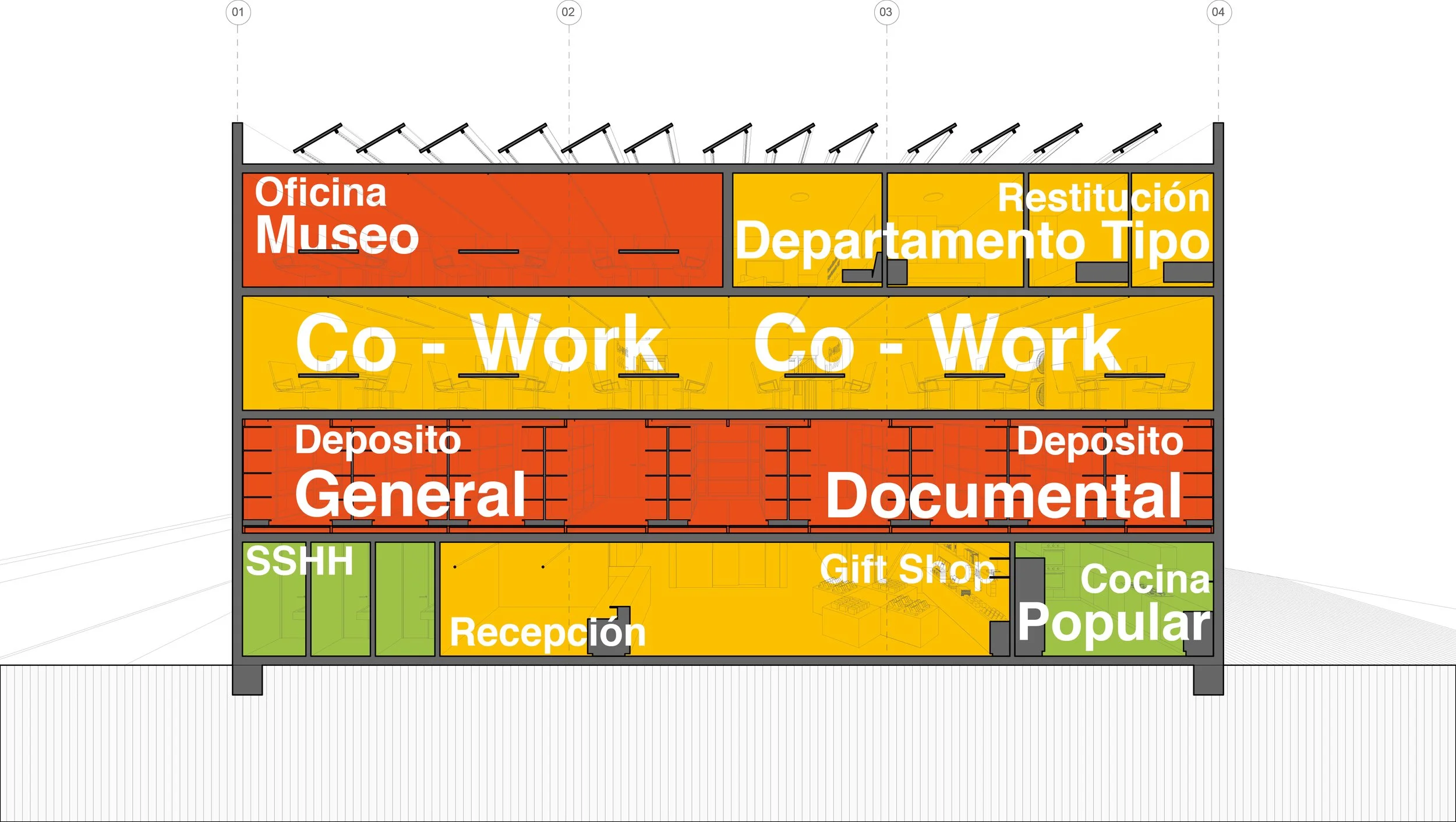

a) The first floor contains the entrance and related service areas: the lobby and reception/ticketing area, restrooms, and the soup kitchen and communal dining room. Since there are no basements, the first floor requires no reinforcement and can therefore fully retain its original characteristics.

b) The second floor is used for storage areas, both general and documentary. This is a strategic play. Considering that the interior height of each floor inside the block is 2.3 m, any structural reinforcement will diminish habitability conditions. Locating the storage areas on the second floor allows for reinforcement of both the second and third floor slabs without directly affecting these floors. Because it is primarily used as an archive and storage area, this floor can function without problems even with limited habitability conditions.

c) The third floor contains the co-working area and is connected to the documentary storage area via a direct staircase. Since the lower floor is already reinforced, it does not require further reinforcement inside.

d) The fourth floor is divided equally between the museum offices and a reconstruction of one original apartment. Due to their private use in the case of the offices, and as public access to the apartment should be restricted to groups of five people at a time, no reinforcement is required.

This layout seeks to enhance the building's public character, but in particular, to transform it into a meeting space for the community. The first floor is enlivened by the soup kitchen, its terrace, the gift shop, and a tree-lined plaza with Wi-Fi facing the north facade.

THE MUSEUM AS A MEMORIAL

The museum's status as a memorial requires thoughtful consideration about the image the intervention on the existing structure will produce. Since the building itself is a testament to the history of the Villa San Luis Complex and the community that inhabited it, it is essential that the intervention clearly differentiates what is new from what is preserved. This idea, then, motivates the project's answer to the third question: how to reinforce?

A stereotomic reinforcement method in reinforced concrete (based on walls and slabs) is ruled out, since the difference between the new and original structures would be difficult to understand, as both share the same materiality and geometric characteristics. Additionally, the dimensions of the elements that make up a structure of this type would considerably reduce interior habitability conditions and make the execution of the work a much more complex and, presumably, costly operation.

The project proposes a reinforcement method using rigid diaphragms of cold-dip galvanized steel. Basically, a skeleton adheres to the areas to be reinforced. Due to its slenderness, the original structure remains visible even in areas with a high density of reinforcement. Furthermore, its material and geometric characteristics—being composed of profiles—make its bracing role evident.

The reinforcement areas proposed are two: the first, and most extensive, encompasses the entire east side of the building, from floors 1 to 4; the second area, is restricted to only the second floor of the west side.

Both interventions fulfill opposing roles in architectural terms:

- The intervention on the east side is expressive. Impossible to hide—due to its size and the program it contains—on the contrary, it embraces its transformative role in the interior space and exhibits its muscularity, revealing the tensions to which the structure is subjected. Additionally, it addresses the reconfiguration of both the vertical circulations—vital in constructing the exhibition's narrative thread—and that of the east façade, the one most affected by the demolitions the structure underwent prior to its declaration as a national monument.

The design of this façade above all avoids falling into historicism and, in line with the principles of modern architecture that shaped the Villa San Luis complex, is resolved in a rational and pragmatic manner, primarily addressing the building's interior functionality, but utilizing contemporary materials and techniques—such as sustainable design methods—giving the building's design an undeniable contemporary appearance. This is also relevant, given that from an urban perspective, the image of this façade enters into a dialogue with the contemporary image of the buildings in the Nueva Las Condes complex, which it faces.

- The intervention located on the second floor of the west side of the building, on the contrary, seeks to disappear. The goal is to concentrate a high structural density within the interior to free the other floors from any additional reinforcement. In structural terms, this translates into a stereometric steel structure confined by the existing walls, beams, and slabs of the second floor.

This strategy not only allows floors 1, 3, and 4 (on the west side) to be maintained virtually in their original condition, but also allows the west façade to be preserved without further intervention. This is of particular importance, since this is the façade that faces the public space, the city. It is only fair, then, that the façade that was spared from demolition—by pure chance, since they could have started demolition with it first—is the one that welcomes citizens who visit the memorial museum.

Based on this, the project proposes restoring this façade, repairing the stucco and repainting the piers that divide the windows based on their original colors. This also creates an interesting counterpoint between the west and east facades: while the former is an architectural testament to the museum's history, the latter showcases its inner life, the movement of visitors, community activity, and culture.

Container and content at the same time.